In February, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) released new guidance [1] aimed at clarifying aspects of regulation for Digital Mental Health Technologies (DMHTs) in the UK. This is the most recent output from a three-year project by the MHRA and NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), funded by the Wellcome Trust, focusing on the regulation and evaluation of these technologies [2-5]. The guidance provides the latest information and helpful clarification to the questions around the definitions of DMHTs and whether they qualify as a ‘Software as a Medical Device’ (SaMD), requiring compliance with associated regulations.

In this blog post, we highlight key messages of the new guidance, provide our views on the strengths of the guidance, what we see coming next and how the guidance relates to the HAWT project currently in progress at Horizon Digital Economy Research at the University of Nottingham.

As noted by Holly Coole, Senior Manager for Digital Mental Health at the MHRA, who leads the Wellcome-funded DMHT project in collaboration with NICE:

“We hope the recently published guidance for digital mental health technology characterisation, regulatory qualification and classification will be useful for resources like the HAWT Toolkit. We recognise that mental health support is often provided through third sector organisations like charities and helping them to understand the regulations is crucial to ensure that safe and effective technologies are adopted that have been responsibly developed. We hope that clarification about what qualifies as SaMD, along with clear examples, can support decision making not just within national health services across the UK but across all sectors and we sincerely value the work that the HAWT project is doing to guide potential adopters and raise awareness of the regulations”.

Overview of the guidance: Useful, but only for DMHT as SaMD

In the UK, the MHRA are responsible for regulating medicines and medical devices. Due to the varied nature and recent development of technologies for mental health, stakeholders were keen for clarification on regulatory approaches and requirements [3]. As a result, the new guidance is aimed at manufacturers to help them answer the question of whether their DMHT is classified as a SaMD.

What is a DMHT?

According to the guidance, DMHTs are “digital and software products designed to support mental health and wellbeing”. Keeping to a board definition, this includes a wide range of different technologies including internet-based or smartphone-based applications, websites, virtual reality (VR) headsets and AI-driven tools for mental health.

Which DMHTs qualify as medical devices?

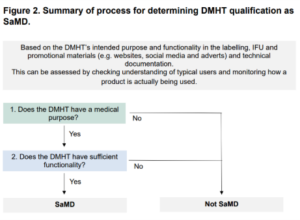

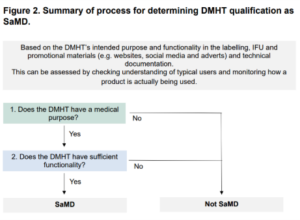

Previously, the MHRA had guidance on qualification and classification for SaMDs, but not with examples for mental health [3]. As DMHTs create a grey area for regulators, the guidance aims to systematically unpack the purpose and level of functionality of the DMHT determining whether it qualifies as a SaMD.

This means that manufacturers must answer the following two questions:

- Does the DMHT have a medical purpose?

- Does the DMHT have sufficient functionality?

Determining Medical purpose:

- To have a medical purpose, the medical devices must perform a clinical task and target clinical conditions and symptoms.

- With reference to the UK Medical Devices Regulations 2002 (SI 2002 No 618, as amended), the medical devices are defined as any instrument, software or other material intended to be used for human beings for purposes including: diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease; diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation of or compensation for an injury; investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological process.

- EU Medical Devices Regulation (2017/745) (EU MDR) covers similar purposes as the above with the additions of prognosis, compensation for an injury or disability, and investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy a physiological or pathological process or state.

- DMHTs are likely to be considered to have a medical purpose if they are intended for one or more of the above purposed or as part of the broad process involved in the management of mental ill health.

Determining Sufficient functionality:

- For DMHTs to be considered SaMD, they need to have a medical purpose and high functionality.

- High functionality: If the function performs computational tasks (other than standard tasks*), such as the following, it is considered high functionality: Processes user instruction with an interactive and / or personalised output; Processes data / information with a calculation / algorithm that is not easily verifiable; Processes data / information using AI.

- *Standard tasks include a) stores data / information without changes b) Communicates data / information without change or prioritisation c) Processes user instruction to show fixed content in a similar manner to a user choosing a chapter in a digital book, audio book or video d) Processes data / information with an easily verifiable calculation / algorithm.

What does this mean for regulation?

If the product classes as a SaMD then further legal requirements need to be considered from evidence generation to risk assessment to certifications to post-market surveillance. The requirements are based on device classification Class I or Class IIa/b or Class III. It is important to note that when placing products in the UK market, there are some differences in regulatory requirements between Great Britain (UK MDR & EU MDD) and Northern Ireland (EU MDR).

Our analysis – The strengths and areas to improve on the guidance and why?

While the new guidance is aimed at clarifying the regulation and evaluation of DMHTs, the guidelines only focus on technologies that may qualify as ‘software as a medical device’ (SaMD) in the UK. The guidance provides a helpful starting point for manufacturers to understand whether their technology is a SaMD and if so, the next steps for regulation and evaluation, but does not focus on non-SaMD technologies thereafter.

Strengths

- There are various examples to help illustrate different applications where DMHTs could be classified SaMD (e.g., see Table 3. MHRA DMHT examples of functions, computational tasks and low / high functionality).

- The distinction between low and high functionality paradigms attempts to detect risks especially related with AI technologies. Additional safeguards are needed when DMHTs attempt personalised recommendations as the human rights’ risks for individuals increase (manipulation and bias).

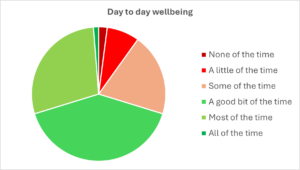

- There appears to be a broader scope of DMHTs with an increased emphasis on wellbeing focused application as well as general diagnosed mental health issues. The guidance includes DMHTs that target wellbeing and sub-clinical levels as well as other technologies involved with managing mental health for those with other conditions.

- The guidance has many practical elements including the easy-to-digest decision maps and the MHRA DMHT characterisation form to help manufacturers define and communicate their device characterisation to the MHRA (and other stakeholders).

- The guidance is generally helpful in the mission to ensuring safe and effective digital mental health interventions.

Next steps?

- Because the MHRA is only meant to regulate medicines and medical devices, there are many DMHTs that this guidance might not be applied to (i.e. those that are not SaMD). This means that there are still gaps in the regulation of DMHTs which must be filled by other regulators like NICE and the NHS [3].

- There is not much discussion on the determination for ‘medical device’ classification. It mentions “this guidance explains how to determine this and how UKCA / CE certification shows compliance with these regulations”, but this is not clear about what actions to follow if the DMHT is classified as a medical advice but does not satisfy SaMD requirements – in other words what do we do following the flowchart from Figure 2 if we land on ‘not SaMD’?

- ‘Medical purpose’ has a very broad definition, so it is likely that most of the DMHTs will fall under this definition, but identifying ‘sufficient functionality’ may not be that straight forward. Especially the distinction between processing data / information with an easily verifiable calculation / algorithm and processing data / information with a calculation / algorithm that is not easily verifiable. Although the paradigms are well drafted, there might be more borderline cases.

- While the guidance is helpful, the title and overview are slightly misleading. The guidance can be better described to reach the audience with a different title and a disclaimer that this is only a piece of a puzzle (i.e., DMHT as SaMD), this is not the guidance for DMHTs as a whole. There are technologies that will sit at the “borderline,” requiring further advice. Furthermore, it could be noted that manufactures have additional regulatory obligations such as data protection regulation.

- Finally, more explanation about what legal principles are to be protected in each occasion and more connection with specific rights (privacy, informational self-determination, non-discrimination, freedom of thought etc) should be considered to better inform the general audience and the manufactures about potential risks and adequate measures.

Horizon Adoption of Wellbeing Technology toolkit

So how does this relate to our project?

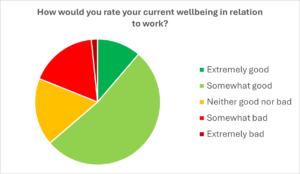

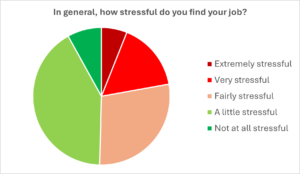

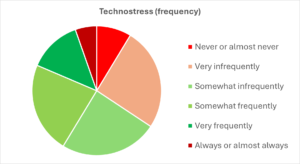

Horizon launched the Horizon Adoption for Wellbeing Technologies (HAWT) project to co-develop a comprehensive toolkit to guide the evaluation and adoption of immersive and emerging technologies for mental health support; so that community and voluntary sector (CVS) organisations can make informed decisions about which technologies to adopt.

So far, the project has conducted a review of the current regulations and guidance for DMHTs from different sources and is in the process of conducting workshops to begin co-developing the toolkit with experts and key stakeholders.

Our toolkit will provide CVS organisations with practical resources to assess different aspects of DMHTs such as relevant legislation, standards and regulations. Therefore, this new guidance from the MHRA will be included to inform the decisions process for adopters of these technologies about considerations for DMHTs that classify as medical devices, instead of the manufacturers. However, the HAWT toolkit will also bring together other guidance and standards for technologies that are not medical devices, such as the NHS Digital Technology Assessment Criteria (DTAC) and NICE Evidence Standards Framework (ESF). This toolkit will bridge gaps in knowledge of DMHTs by providing a comprehensive toolkit of relevant topics, compliance and considerations to allow CVS organisations to check if the DMHTs are right for them.

Additionally, members of our HAWT team were involved in the organising, planning and facilitating of an MHRA event earlier this year which focused on bringing together experts to discuss AI for Mental Health. Dr Aislinn Gomez Bergin, Professor Elvira Perez Vallejos and Lucy Hitcham presented their research findings on digital mental health technologies and facilitated workshops with those in attendance on what should be considered when regulating and evaluating these technologies. We hope to carry on this work with the development of the HAWT toolkit. Stay tuned!

References

[1] Digital mental health technology: Qualification and classification. (2025, February 13). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-mental-health-technology-qualification-and-classification

[2] Digital mental health technology. (2024, May 3). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/digital-mental-health-technology

[3] Hopkin, G., Branson, R., Campbell, P., Coole, H., Cooper, S., Edelmann, F., Gatera, G., Morgan, J., & Salmon, M. (2025). Building robust, proportionate, and timely approaches to regulation and evaluation of digital mental health technologies. The Lancet Digital Health, 7(1), e89–e93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(24)00215-2

[4] Hopkin, G., Coole, H., Edelmann, F., Ayiku, L., Branson, R., Campbell, P., Cooper, S., & Salmon, M. (2025). Toward a New Conceptual Framework for Digital Mental Health Technologies: Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health, 12(1), e63484. https://doi.org/10.2196/63484

[5] Hopkin, G., Branson, R., Campbell, P., Coole, H., Cooper, S., Edelmann, F., & Salmon, M. (2024). Considerations for regulation and evaluation of digital mental health technologies. DIGITAL HEALTH, 10, 20552076241293313. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076241293313